Home > Off the Charts > A Tale of Two Digital Economies: Gig Workers and Remote Workers

A Tale of Two Digital Economies: Gig Workers and Remote Workers

The pandemic’s evolution and states’ varying policy responses have shown that digitally ready states benefited from both a labor force that could socially distance and work from home, as well as one that could support the delivery of essential services in such a scenario through the availability of gig workers. These past months have demonstrated the gig economy’s increasing importance in providing essential services to communities, while also highlighting the inherent disparities and vulnerabilities experienced by gig workers.

Key Observations and Insights

In an earlier segment, we explored how digital readiness across the 50 states and the District of Columbia impacted their capacity to implement social distancing policies with relatively less impact on employment numbers. Access to digital devices (computers and smartphones) and broadband internet and greater employment in low-touch, high-tech jobs (such as information technology and financial intermediation) allowed several highly-urbanized states to reduce workplace mobility and implement longer stay-at-home policies.

We now turn to another aspect of the digital economy – gig workers – who through their continued provision of essential services, supported the ability of others to stay at home and maintain social distancing.

Who is a Gig Economy Worker?

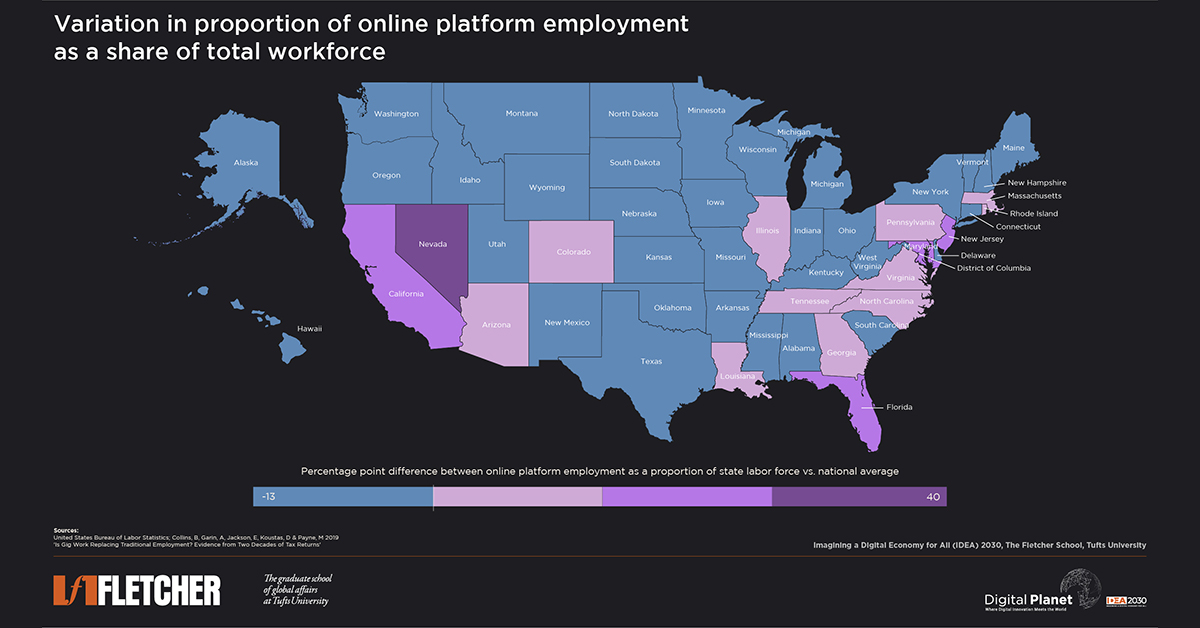

While there is no standard definition of a gig worker, it is commonly understood to comprise members of the labor force with contingent or alternate work arrangements––including independent contractors, on-call workers, and workers provided by temporary help agencies and contract firms. Amongst such workers, online platform employees or those with electronically mediated employment find jobs through online platforms and can render them either offline (such as Grubhub, Uber, Task Rabbit) or online (such as Amazon Mechanical Turk). The past decade saw the gig economy balloon by 6 million people, driven primarily by a proliferation of platform-based services; indicating a broader economic and demographic shift in the nature of work. At a national level, online platform employment constitutes less than 1% of the workforce (most recent official numbers by the IRS and BLS only date back to 2016), though the sector has been rapidly growing, with states like California, Illinois, Maryland, and New Jersey leading the pack.

Gig Work Platforms, Digital Readiness, and Support for Social Distancing

States with high digital readiness scores (a composite index of work from home capacity and inclusive internet and digital public services) also have a higher proportion of gig workers on digital platforms. Last mile delivery services provided by gig workers played a critical role in supporting longer stay-at-home policies which enabled states to maintain a low average transmission rate between March and May 2020. It is not a coincidence that these states witnessed both higher than national average reduction in workplace and transit mobility and mobility for essential goods and services (grocery stores and pharmacies).

Digitalization has facilitated remote work i.e., low-touch tech-enabled high-income jobs that could be performed from anywhere and gig work on digital platforms — workers whose efforts on the frontline continue to support social distancing nearly a year into this pandemic. While digital growth has brought increased and more flexible employment opportunities to the labor force writ large, the nature of those jobs and contracts still reflect a widening disparity.

Gig Work during COVID-19: Increased Hiring in Essential Service Delivery Jobs

COVID-19 has left over 10 million Americans unemployed since March 2020 but has also made gig work more popular as workers seek to supplement income or lost jobs. However, the impact within sectors providing gig work has been varied, with some seeing higher unemployment and income reductions than others. According to data by Steady, a listing site for online gig opportunities, workers in restaurant, pharmacy, and grocery delivery, saw increases in income, while those working for ride sharing platforms, house cleaners, or in the hospitality industry faced a sizeable or complete loss of income.

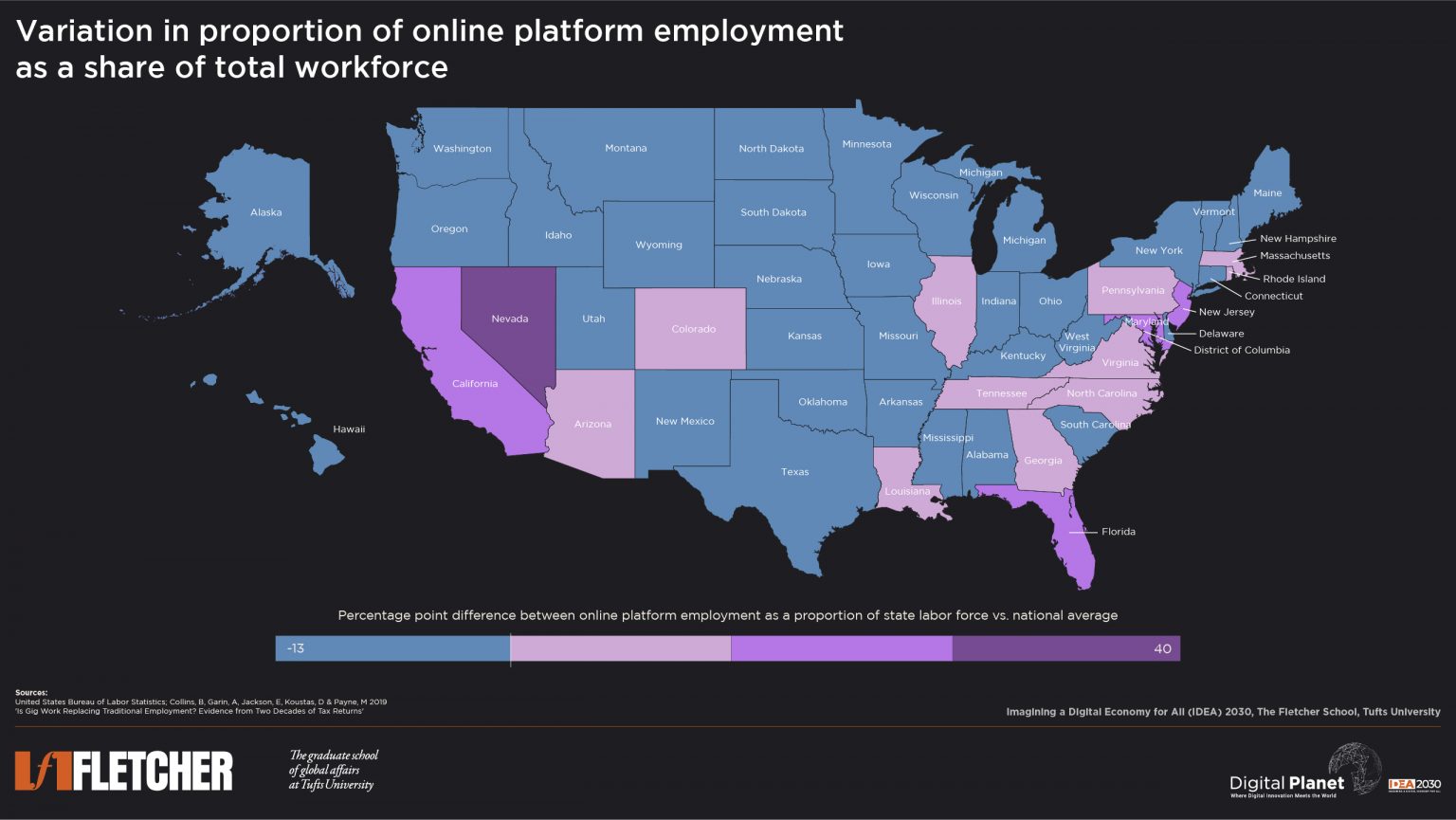

As grocery delivery service apps saw record downloads coinciding with the implementation of stay-at-home orders across states, delivery platforms responded with increased hiring of online gig workers. Instacart responded to a demand increase by hiring 300,000 additional personal shoppers during March and April and subsequently announced plans to hire 250,000 more. This demand was especially concentrated in states like California, New York, Texas, Florida, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Virginia, New Jersey, Georgia, and Ohio. Available data show 27,000 new workers were hired in New York, 12,000 in New Jersey, and 15,000 in Illinois. Amazon hired 175,000 seasonal employees when the pandemic was at its peak from March to April, and added thousands of new jobs in Massachusetts and Illinois.

Digitalized and Vulnerable

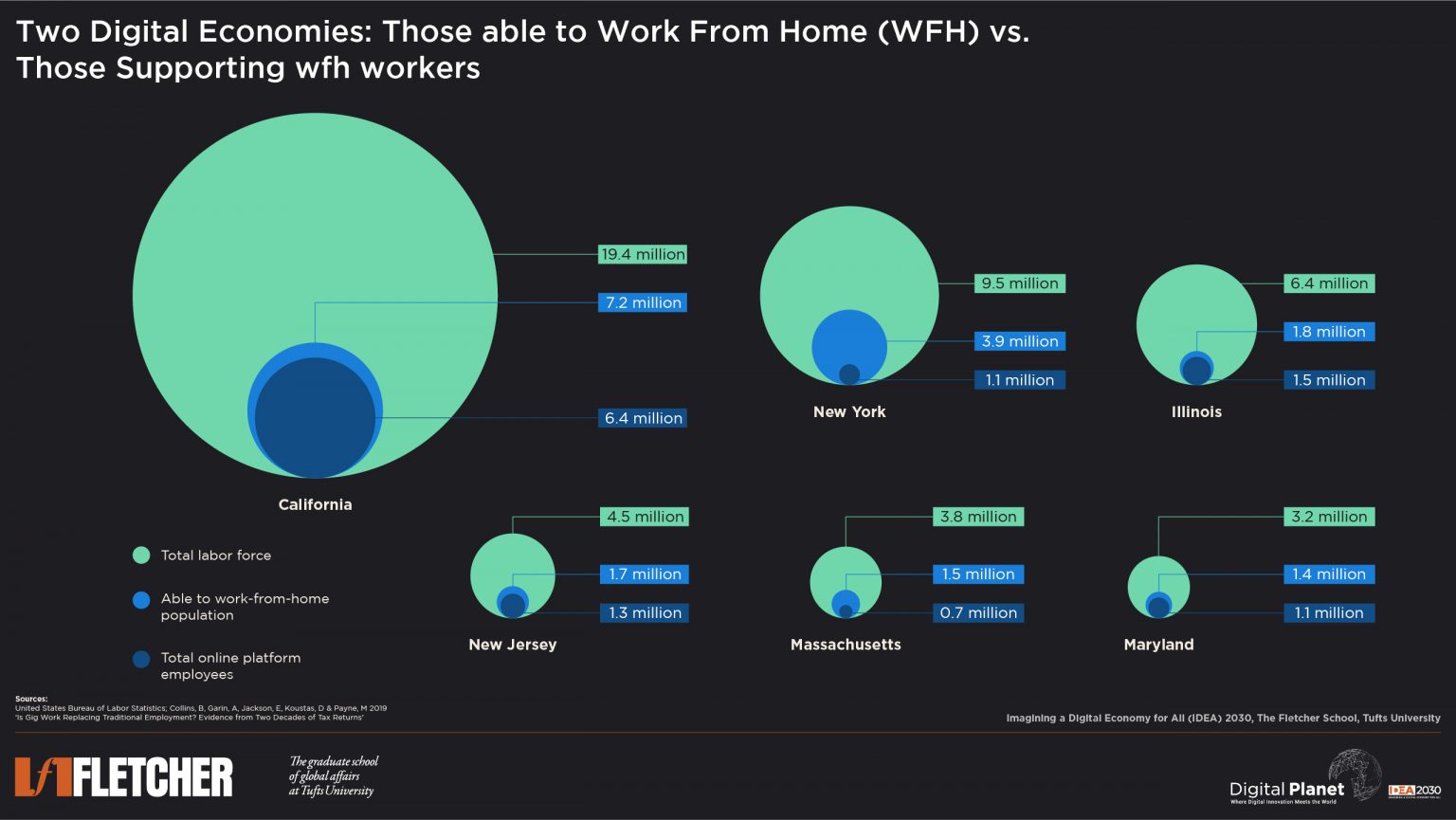

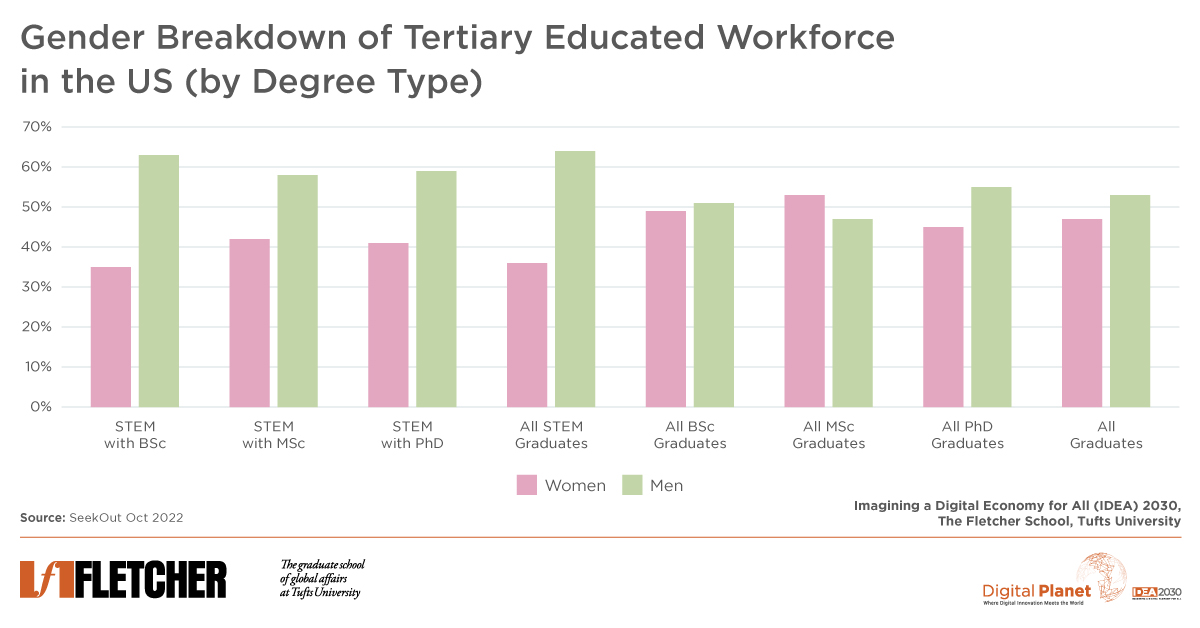

Gig workers are likely to be more vulnerable than their remote work counterparts in terms of income, stability, and regularity of payments, as well as access to benefits such as healthcare insurance and paid time off. Within this group, women and Blacks are likely to be more disadvantaged than the rest. Blacks form only 12% of the total workforce but make up 17% of all electronically mediated workers and 23% of all in-person electronically mediated workers. In this pandemic, Black gig workers more exposed to health risks on the job and have lower financial and legal security because of the nature of gig work contracts. While the gig economy has allowed more women to enter the workforce, the gender pay gap exists in traditional employment and persists in the gig economy as well, despite the absence of labor segregation and inflexible work arrangements. In the current pandemic, this again puts women, and especially those from minority race/ethnic backgrounds, in more financially precarious situations.

The 2008 financial crisis was a defining moment for the gig economy––the housing markets’ collapse and rising unemployment created a shift in the American workforce, which started accepting temporary, short-term, and flexible employment opportunities. The COVID-19 pandemic is set to become another key point in the gig economy’s evolution. On the one hand, the sector kept the US economy afloat by continuing to provide essential services, while absorbing the newly unemployed and those in to ensure income smoothing. On the other hand, the pandemic also exposed the disparities faced by those within the sector––from a lack of legal enforcement of labor standards, to inconsistent financial support and absent health benefits. As policy makers and private enterprises adjust to new norms of socially distant employment, it is imperative to consider the condition of gig workers and provide necessary safeguards. While voters in California passed Proposition 22 in the November election, which leaves gig workers without employee protections, states such as Massachusetts, Maryland, Illinois, New Jersey, and Washington, among others, have adopted some form of the expansive “ABC” definition of who is an employee with no exclusions for “gig” workers, and Seattle recently passed an emergency ordinance for such online gig workers to be provided sick pay. The state of safeguards for gig workers remains very much uneven across the country.

Research Methodology

Online Platform Employment Estimates

Baseline data on gigs mediated through online labor platforms was obtained from the research paper Is Gig Work Replacing Traditional Employment? Evidence from Two Decades of Tax Returns. / Collins, Brett; Garin, Andrew; Jackson, Emilie; Koustas, Dmitri; Payne, Mark. 2019. Estimates for 2019 were arrived at using 5-year CAGR from the data presented in the paper.

Work from Home Population Estimates

State Employment estimates were obtained from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019). The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) was utilized to arrive at a list of employment categories that can be performed from home.

All data and sources are available here.

Digital Planet Graduate Analyst Madhuri Mukherjee and Undergraduate Analyst Heidy Acevedo worked on this analysis under the guidance of Bhaskar Chakravorti, Ravi Shankar Chaturvedi, Christina Filipovic, and Joy Zhang at Digital Planet, The Fletcher School, Tufts University.

This research is a part of the IDEA 2030 initiative, made possible by the generous support from the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth