Home > IDEA2030 > Uneven State of the Union > Turning America’s Digital Divide into Digital Dividends: Policy Recommendations for the Biden Administration

Turning America's

Digital Divide into

Digital Dividends

Policy Recommendations for the

Biden Administration

UPDATE: Our updated analysis, state and city broadband maps, and data dashboard can be found here.

At the height of the pandemic, millions of Americans learned that they would be receiving stimulus checks of up to $1,200 as a small buffer against the financial hardship many were facing. Over half of survey respondents said they planned to use the money to pay bills or buy basic essentials like food. Within two months, 159 million Americans had received these payments, yet many of the poorest and most vulnerable had to wait much longer for checks or debit cards, some of which never arrived. Those who never received their payment—disproportionately “non-filers” who are lower income and not beneficiaries of programs like Social Security—were told by the IRS to fill out a digital form online. One major barrier to this solution: lower income people are less likely to have internet at home, and the connection spots like schools and local libraries they had relied on in the past were closed. A year after the first round of stimulus checks were announced, up to 8 million Americans had not received the payment to which they were entitled.

Americans are more reliant on the internet than ever. Yet access remains far from equal. As the pandemic highlighted, high-speed broadband is a necessity to work, learn, shop, and connect with one another. Digital inclusion is not only an added source of resilience in times of crisis, but it is the first step toward financial inclusion for the most vulnerable Americans. It’s a necessity for children who increasingly rely on the internet to do their homework and advance academically. Those on the wrong side of the digital divide find it hard to access the same economic opportunities available to their connected peers.

Compared to our global peers, the US is lagging on cost, speed, and access to the internet. After years of inaction and delay, Congress has finally reached a compromise, and is committing billions through the infrastructure bill to expand broadband access across the nation. Now the work of allocating those resources begins. Unfortunately, we still do not have a clear picture of the digital divide. What we do know is that current commitments are far below what is actually required—$240 billion—to achieve universal broadband. What steps might the Biden administration take to bring clarity, more resources, and progress to the challenge of the digital divide?

Techonomy Talk: How America's Digital Divide Adds Up: A Report on Connectivity

Our state of understanding on access to broadband nationwide is muddled due to inaccurate, outdated data. While the FCC estimates that 14.5 million Americans do not have access to broadband at 25/3 Mbps, a more thorough “manual” check by BroadbandNow put the number at 42 million. Microsoft estimates that nearly half the country does not use the internet at broadband speeds. Despite the lack of clarity coming from the government on the true extent of the digital divide, a consistent estimate emerged on the budget to close the digital divide: $100 billion. This number was put forth most recently by President Biden’s American Jobs Plan, but echoes a similar proposal from Democrats for $94 billion. However, this budget is based loosely on a past FCC estimate of what it would cost to bring universal broadband to the country: $80 billion. That FCC calculation relied on the drastic undercount of 14.5 million unserved Americans. Applying the same methodology to BroadbandNow’s more thorough accounting of the divide brings a more sizeable figure of $240 billion.

The current FCC—finally empowered with the funding required—is making up for lost time through developing more comprehensive broadband maps. Simultaneously, the Biden administration effectively rejected the older FCC maps, and released maps with “key indicators of broadband needs across the country.”

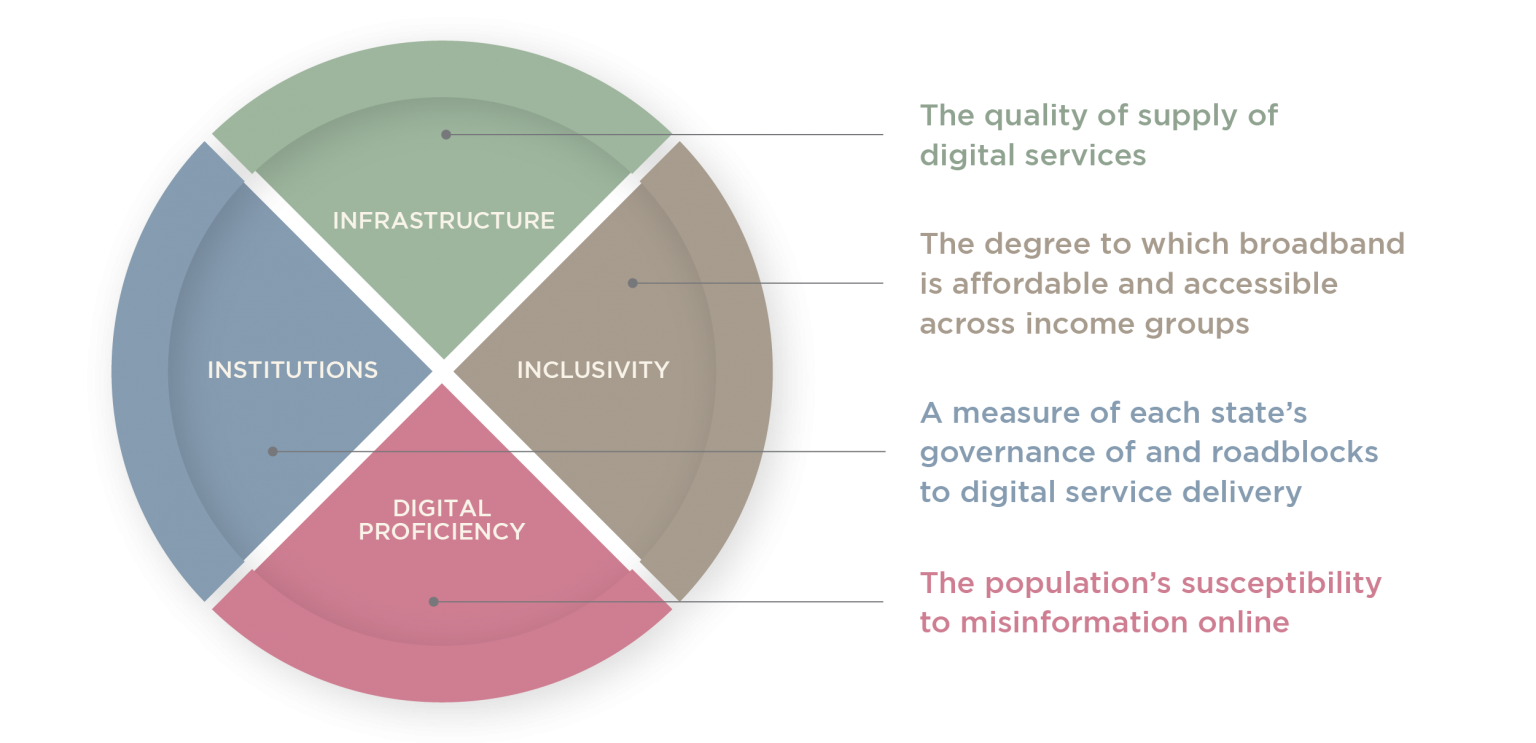

At Digital Planet, we identified key facets of the digital divide: access, inclusion, institutions and digital proficiency. We also examined racial, socioeconomic, and urban-rural distributions, and used this analysis to work toward clarifying the nature and extent of the digital divide in the United States. The maps below, based on a combination of the best available data, organized at the state and county level, offer snapshots of the divide and how it varies across the country.

The federal government can set a nationwide framework, develop policy guidelines, secure budgets, and offer incentives, but the barriers to digital readiness and solutions must be identified at a state and local level.

Internet service providers have few incentives to expand service in rural communities, creating an access gap. At the same time, an estimated three times as many metropolitan households as rural households lack broadband subscriptions—suggesting an additional affordability gap. Improved data collection—spearheaded by the FCC—can help states develop a more intelligent and informed broadband strategy that will consider local realities and cater to local needs. The status quo—woefully inadequate and inaccurate broadband maps—hits tribal and low-income communities the hardest.

Each state has different issues and different barriers to dismantle. Some, such as Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, Alabama, and West Virginia, with less than a third of their populations with basic broadband access, should be prioritized for investments in access infrastructure. Others, such as Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Nebraska have seen lobbying efforts create roadblocks to public sector alternatives such as municipal broadband. Still others lack a coherent broadband strategy entirely, or the political will to see it through. Across all these states, they must be given targets depending on the barriers that they must take down, with incentives and resources to achieve those goals.

While the FCC works toward giving the country a clearer picture of the true state of the broadband gap, we cannot wait to move forward on securing resources and developing a strategy for the deployment of those resources. The policy recommendations below lay out a path to achieving a more inclusive internet in the United States: transforming America’s digital divide into digital dividends.

Digital Divide Across the 50 States

million people

million people

Number (or percentage) of people in urban or rural counties not using the Internet at broadband speeds, as of November 2019 . Broadband speed as defined by the FCC is at least 25 Mbps/ 3 Mbps. Urban and rural gap is defined by people living in urban, mostly rural and completely rural counties as defined by the US census. (Source: Microsoft)

Infrastructure

Internet Speed

Policy Recommendations

1. Close the access gap through better data, a larger budget, and more informed planning

Methodology: $240 billion to close the broadband gap

Our methodology for deriving an accurate estimate of the cost to close America’s broadband gap first determines the degree to which the FCC data underestimates the rural and urban broadband gap by state, and then multiplies the FCC state-by-state cost estimates to adjust for the relevant degree of miscalculation.

To find the rate at which the FCC underestimates both the rural and urban gap in each state, we compare BroadbandNow’s more accurate broadband data to FCC-reported data, at similar times of collection (2019).

We then multiply the FCC cost analysis by state with the rate of underestimation. Cost estimates by state are then broken down into rural and urban components, accounting for the assessment that providing rural coverage is 1.27x more expensive than urban.

2. Close the affordability gap through modernizing the Lifeline program and supporting digital equity offices

Reform the Lifeline program: expand participation, increase the subsidy, and improve plan quality. Support local solutions through funding digital equity offices across the states.

Broadband access in the US is among the most expensive anywhere in the world. The Ajit Pai-led FCC’s decision to roll back net neutrality has made it possible for broadband companies to charge more for certain services or content. Current affordability solutions are sub-standard. Lifeline—a federal program created in 1985 aimed at low-income Americans—offers such poor service and contains so many restrictions that only 1 in 4 of the more than 33 million eligible households actually take advantage of it. Lifeline is the only current, long-running federal program directly addressing the affordability gap at the household level, offering subsidies and low-cost smartphone or broadband plans to consumers. To increase enrollment, individuals should automatically be enrolled when they are given other government benefits, like SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) or Medicaid. The current benefit ($9.25 a month for broadband) is drastically insufficient, given that monthly broadband costs on average between $68.36-$83.41, which makes up for only 13% of the average advertised price in the US. A more generous benefit will encourage more program participants to join. Shortly after the Emergency Broadband Benefit (EBB)—a temporary, pandemic-era program establishing a $50/month home internet subsidy—went into effect, the eligibility website temporarily crashed due to its popularity. As of late June 2021, the EBB has over 2.77 million enrollees. Through expanding the base of companies that pay into Lifeline beyond landline and wireless phone providers, the program could increase the subsidy, reach sustainability, and expand enrollment—living up to its name.

E-Rate is another program worth reimagining. While the stimulus funding of $7.2 billion towards the Emergency Connectivity Fund is a welcome change to expand the E-rate program beyond the walls of schools and libraries and into homes to bridge the homework gap among students attending school remotely during the pandemic, long-term funding solutions to permanently bridge the digital divide must be adopted. A recent report estimates that keeping students connected at home will cost up to $11 billion in the first year and up to $8 billion annually thereafter. Furthermore, in order to close the divide for teachers, an additional cost of $1 billion is needed in the first year.

While a lack of broadband access in rural areas captures the attention and sparks discussion among elected representatives, the adoption gap is 3 times as wide among urban households as rural households. The more urban the area, the wider the variation in broadband adoption—suggesting affordability as the primary barrier to adoption in urban areas. Our past work highlighted how Black and brown households have less access to broadband internet and laptops than white households. Improving affordability, access, and digital skills requires local focus and support. During the pandemic, local governments and civic organizations stepped in to creatively find solutions to the broadband gap. Pre-pandemic, states were stepping up to fill the gap left by the federal government through developing strategies to expand broadband access. Given the current dearth of credible and timely data around access, affordability, and digital proficiency from the FCC, states and localities must be engaged and supported in their efforts to close the digital divide.

Local digital equity offices offer one solution. These offices can work collaboratively across state and local government agencies, partner with community groups, and work to identify which gaps—access, affordability, or digital literacy—are most pressing in which areas and help to design appropriate solutions.

3. Invest in digital literacy and skills-building

Equipping the public with digital skills and tools will not only help people fully realize the benefits of broadband, but will add a layer of protection against increasing cyber-attacks and misinformation.

Outside of cost and access barriers, digital literacy and perceived relevance play a role in preventing consumers from coming online. While the pandemic may have spurred a greater interest in digital tools among some consumers, developing digital literacy and expanding proficiency will foster a more inclusive digital space.

A 2017 Pew Research Center study concluded that the growth of misinformation requires significant attention “urging a bolstering of the public-serving press and an expansive, comprehensive, ongoing information literacy education effort for people of all ages.” Similarly, a study undertaken by the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions found that deficits in digital literacy are among the key sources of vulnerability to digital interference in democracies. In order to combat such disparities, it is critical that digital literacy become part of the discussion around closing the digital divide.

Digital literacy is not simply about understanding how to use technology and common digital tools, but it requires the critical thinking and contextual knowledge to recognize the negative aspects of the online environment, like misinformation and phishing attempts. Developing digital proficiency is a lifelong learning process, where government and the private sector can support users.

Cities and localities recognize the need for digitally literate communities and are investing in developing more digitally proficient populations. Austin, Nashville, and Louisville all have “digital inclusion” funds to help low-income people improve their understanding of computers and the internet. Charlotte and Providence use “digital navigators” to provide one-on-one assistance for those who need it. Microsoft offers free digital literacy courses online, which are used by schools, nonprofits, and governments. Cyber Seniors connects young, tech-savvy people with support and training for senior citizens, not only helping them to improve their digital skills, but also reducing social isolation. Schools are beginning to teach cyber hygiene courses, with curricula available for grades K-12. Innovative solutions to improve digital proficiency are sprouting up too, like Digital Public Square, which created an online game to fight pandemic-related misinformation.

While localities recognize the need for digital literacy programming, they also require the budgets to expand solutions. Both New York and Maryland are using American Rescue Plan funds to expand digital inclusion, and are thinking beyond basic access. The federal government must also recognize digital inclusion goes far beyond a wi-fi signal, and support community-led efforts to improve digital proficiency.

4. Upgrade the standard to 100Mbps

Raise the standard for high-speed broadband to match 21st century uses of the internet: 100 Mbps for both download and upload speeds will future-proof current investments.

The pandemic has only underscored the importance of fast, reliable, and low-cost internet access, as the digital divide continues to persist for millions of Americans. The FCC’s standard of 25 Mbps in download speeds and 3 Mbps in upload speeds is not only outdated, but lags behind digitally advanced nations like Estonia, Singapore, and Switzerland. For example, Zoom recommends an upload speed of at least 3.8 Mbps just for a single connection, let alone the multiple calls that typically occur in a single household on a daily basis. An estimated 74 percent of Americans with access to broadband pay for 100Mbps or faster, and that number is expected to grow to 90 percent within the next five years. With an average U.S. household using five devices, and nearly one-in-five households using at least 10 devices, a faster speed and higher standard of up to 1000 Mbps or 1 Gbps is what the market is demanding, and what the future requires.

As four U.S. Senators recently suggested, earmarking federal dollars towards deploying broadband networks capable of providing high-quality internet access, with low latency and increased reliability, will help ensure that U.S. broadband infrastructure meets the demands of modern and emerging uses of technology: from telehealth consultations and remote learning to the burgeoning Internet of Things and smart-grid applications.

Our past work has shown that the growth in tech jobs tends to cluster more in places with high costs of living and high levels of digital readiness—raising the bar and expanding access to high-speed broadband across the nation can help de-cluster the tech sector and generate inclusive growth dividends more evenly.

Future-proof broadband will be pricey—even our estimate of $240 billion would increase with this higher standard. At the same time, investing in second-rate service is a waste of taxpayer money. With improved data and mapping on access and speeds, the administration will have a better sense of the true cost of universal, high-speed broadband, and will need additional revenue sources to achieve it.