Home > Off the Charts > Uneven State of the Union

Digital Health Divide

Disparities in broadband access prevent telehealth policies from reaching millions of Americans

Summary

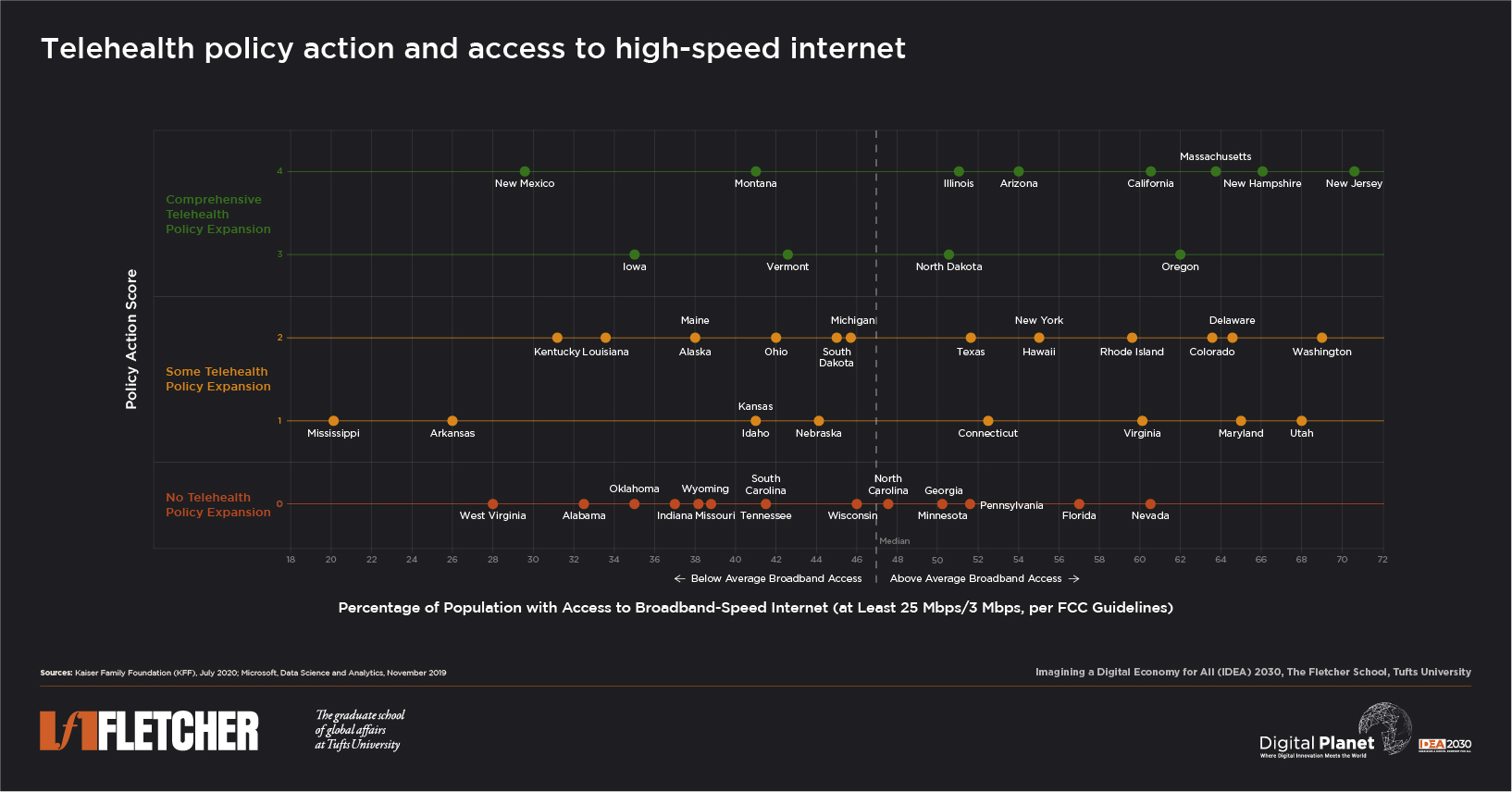

While states have been quick to expand telehealth policies in response to the pandemic, there exists a disconnect between policy action and the infrastructure available to support access. Sixteen of the 34 states with expanded telehealth policies have below-average coverage of broadband-speed internet connectivity—a major impediment to digitally administered healthcare.

Key Observations and Insights

While states have been quick to expand telehealth policies in response to the pandemic, there exists a disconnect between policy action and the infrastructure available to support access. Sixteen of the 34 states with expanded telehealth policies have below-average coverage of broadband-speed internet connectivity—a major impediment to digitally administered healthcare.

COVID-19 has fundamentally changed the way we work, learn, and seek healthcare. With stay-at-home orders being reinstated in an effort to contain the virus spread, access to internet has become a vital lifeline in moving large portions of the American workforce to remote environments, establishing digital learning access for students, and expanding use of telehealth services for patient care. These shifts to a digitally dominant lifestyle have exposed persistent digital divides and broadband deserts that exist in the country. Even with policies to better enable people to work, learn, and receive healthcare from home, the current broadband infrastructure is insufficient and inequitable, and this threatens to widen gaps in access to digitally administered healthcare.

According to the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, ending the week of July 7, 2020, 40% of American adults had delayed or not received needed medical care in the preceding four weeks because of the coronavirus pandemic. Simultaneously, the volume of telehealth claim lines in the US increased by over 8000% between April 2019 and April 2020, and the increase was seen across all regions of the country and in both rural and urban areas, according to FAIR Health’s Telehealth Tracker.

State governments have sought to promote medical care by expanding telehealth-focused policy actions and mandates in response to the pandemic. As of 14 July 2020, 34 states (and the District of Columbia) had expanded their telehealth policies, some more broadly than others. According to Kaiser Family Foundation’s analysis of state executive orders, insurance bulletins, and legislation, an expansion in telehealth policy includes all, or some combination, of the following mandates:

- New requirements for coverage of telehealth services (requiring that insurers cover additional services via telehealth)

- Reimbursement parity for telehealth and in-person services (requiring that insurers reimburse providers for telehealth services at the same rate as in-person services)

- Expanded options for delivery of telehealth services (allowing for additional modes of delivering telehealth services, such as audio-only services, or eliminating barriers to access to telehealth services, such as regulations requiring prior patient-provider relationship)

- Waiving/limiting cost-sharing for telehealth services

We at Digital Planet assigned a Policy Action Score to each state based on the degree of comprehensiveness of their telehealth policy action expansion since the onset of the pandemic. A score of 0 implies that the state has not yet expanded its telehealth policy (as on July 14, 2020), a score of 1 or 2 indicates some telehealth policy expansion, and a score of 3 or 4 indicates comprehensive telehealth policy expansion.

A crucial accompaniment to the expansion of telehealth policies is ensuring the availability of high-quality internet access to all populations within a state. According to research by Microsoft, only 52% of the US population has access to internet at broadband speeds. An estimated 157 million people in the United States do not have access to broadband, which the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defines as high-speed, reliable internet with download speeds of at least 25 megabits per second (Mbps) and upload speeds of at least 3 Mbps.

Compared to download speeds in other developed countries like Japan (102.38 Mbps), Luxembourg (375.78 Mbps), or South Korea (86.98 Mbps), the US lags far behind, with an average download speed of 55.07 Mbps. Moreover, only 25 states in the US have reached the level where more than 50% of the population can access basic 25 Mbps broadband, and other states have even lower rates of access (in Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, Alabama, and West Virginia, less than a third of each of the populations is connected to FCC-recommended broadband-speed internet). Even in New Jersey, which has better internet access compared to other states, almost 30% of the population lacks access to broadband-speed internet.

Of the 34 states that expanded their telehealth policies, only eight have comprehensive policies (Policy Action Scores of 3 or 4) as well as the above-average broadband access needed to enable actual use of these services. These states are best positioned to support their populations in accessing telehealth quickly and equitably. Sixteen states that have expanded telehealth policy also have below-average broadband connectivity—a major impediment to any telehealth policy action, regardless of the policy’s level of comprehensiveness.

North Carolina, Georgia, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Florida, and Nevada introduced no telehealth policy expansions in response to the pandemic, despite a higher proportion of their populations having access to broadband-speed internet. Several of these states, including Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina, also have among the highest number of uninsured individuals in the country (almost 20% of the uninsured live in these three states, according to Kaiser Family Foundation’s analysis). By not mandating an expansion in telehealth policy, these states are effectively leaving the uninsured and the poor with little alternative but to pay out-of-pocket for these services, further exacerbating their financial and health burdens.

Even more vulnerable are the nine states with no expansion of telehealth policies coupled with below-average broadband access: West Virginia, Alabama, Oklahoma, Indiana, Wyoming, Missouri, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Wisconsin. These states risk deepening disparities in medical care and/or disproportionately burdening their healthcare systems if they are not able to introduce, in a timely manner, a plan to better support access to telehealth services and connect more of the population to broadband infrastructure.

Additionally, the 37 states that had adopted the Medicaid expansion as of February 2020 had an average telehealth Policy Action Score of 2.08, compared to an average score of 0.43 among the 14 states that had not adopted the Medicaid expansion.

Expanding telehealth policies is a much-needed step in the right direction and should continue to be mandated even after the threat of COVID-19 passes. However, even within states with greater (although still insufficient) access to broadband, there exist stark socioeconomic and racial digital divides. In the long run, telehealth can increase access and equity—but only if the right investments are made in improving corresponding access to digital infrastructure to bridge the glaring gaps revealed by the pandemic.

Research Methodology

Policy Action Score:

Using Kaiser Family Foundation’s analysis of state executive orders, insurance bulletins, and legislation as of July 14, 2020, Digital Planet assigned a Policy Action Score to each US state based on the degree of comprehensiveness of the state’s telehealth expansion policy action in response to the pandemic.

States’ expansions in telehealth policy include all, or some combination, of the following mandates:

- New requirements for coverage of telehealth services (requiring that insurers cover additional services via telehealth)

- Reimbursement parity for telehealth and in-person services (requiring that insurers reimburse providers for telehealth services at the same rate as in-person services)

- Expanded options for delivery of telehealth services (allowing for additional modes of delivering telehealth services, such as audio-only services, or eliminating barriers to access to telehealth services, such as regulations requiring prior patient-provider relationship)

- Waiving/limiting cost-sharing for telehealth services

A score of 0 implies that the state has not yet expanded its telehealth policy. A score of 1, 2, 3, or 4 is assigned based on whether the state has implemented one, two, three, or all four of the mandates in its expansion of telehealth policy. Scores of 3 or 4 are defined as “Comprehensive Telehealth Policy Expansion,” while scores of 1 or 2 are defined as “Some Telehealth Policy Expansion.”

Population with Access to Broadband:

Proportion of people per state that use internet at broadband speeds, as of November 2019, was obtained from Microsoft Data Science and Analytics. Broadband speed as defined by the FCC is at least 25 Mbps/3 Mbps.

All data and sources are available here.

Digital Planet Graduate Analysts Patrick Béliard, Malavika Krishnan and Devyani Singh; and Undergraduate Analyst Heidy Acevedo worked on this analysis under the guidance of Bhaskar Chakravorti and Joy Zhang at Digital Planet, The Fletcher School, Tufts University.