Semiconductor blockades are powerful sanctions—but may not prove effective with Russia.

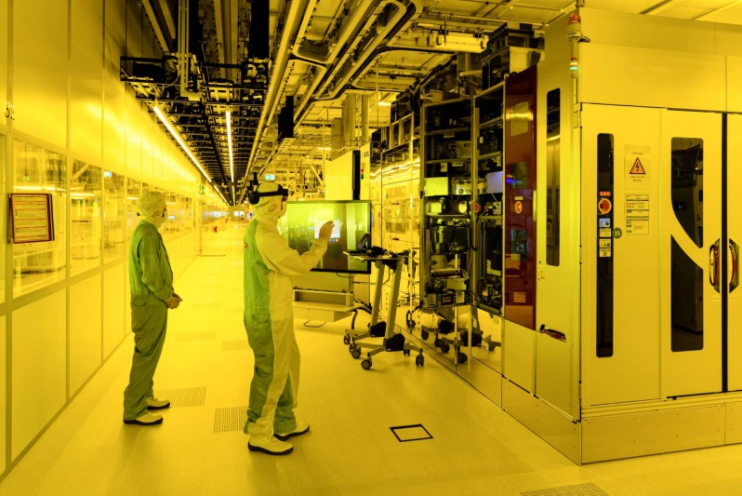

As the poker game over Ukraine has the world on edge, U.S. President Joe Biden warned Russian President Vladimir Putin last week that the United States would act “decisively and impose swift and severe costs” on Russia in the event of an invasion. What might these severe costs be? In late January, the Biden team hinted at one novel sanction: The United States would play poker with real chips, the kind that powers everything from smartphones to military drones and supersonic jets. According to an unnamed senior administration official speaking in a White House press call, cutting Russia off from any semiconductor chips made with U.S. inputs (which include chips made in Taiwan and elsewhere) would have “massive consequences that were not considered in 2014”—the last time Russia invaded Ukraine.

This move pulls from Biden’s predecessor’s playbook. In 2020, then-U.S. President Donald Trump used the Foreign Direct Product Rule to block Huawei, the Chinese telecommunications giant, from purchasing U.S. products as inputs, causing the company’s revenues to fall by 31 percent in 2021 as a result. Might the same strategy work to keep an entire country in line? There are reasons to be doubtful, given the industry’s hard realities and the complex geography of its supply chain.

Consider three questions. How much control does the United States have over the world’s chip supplies? How much pain would a chip blockade inflict on Russia and Putin? How credible is the threat?